Chicago, Illinois

Last week, we had the pleasure of speaking to the Chicago Art Deco Society at the former Jane Addams Homes housing project about a lovingly remembered courtyard sculptural collection conceived and designed by Edgar Miller in the late 1930s. Pure deco in design, with Miller’s stylistic flourishes, these sculptures are currently in storage awaiting restoration for the work-in-progress National Public Housing Museum, which hopes to incorporate the sculptures back onto the site. The NPHM is currently raising the remaining funds to rehab and remodel the last remaining structure of the project, at 1322 West Taylor Street, into a museum somewhat similar to the Tenement Museum in New York City. The museum would tell the stories, through recreated tenants’ rooms, of what it was like to live and grow up in these then-revolutionary housing structures, while dispelling some of the stereotypes of public housing being a total blight and failure on our urban fabric.

Chicago Historical Society

The Jane Addams Homes public housing project— the first completed in Chicago in 1937 and named after the then-late activist reformer— was funded by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a branch of FDR’s New Deal, which was implemented to help the US crawl its way out of the Great Depression. Astonishingly, at the time, the government also saw the value in funding art projects for these developments, and art projects for other government buildings, as a way to provide relief to struggling artists all over the country who remained committed to their craft in spite of the seemingly hopeless lack of capital to keep large-scale art projects going. The main agency in charge of this funding and resource allocation was the Temporary Relief for Artists Program (TRAP).

While it doesn’t seem as if Edgar came running for a handout— he was already gainfully employed and not in need of relief— the architecture firm Holabird & Root, which was hired to design and construct the Jane Addams Homes, in 1936 suggested Miller to the bureaucrats in Washington, DC, as the perfect artist to come up with the complimentary art to their innovative apartment project design. Of course, we’ve already discussed Miller’s close connection with the principals of Holabird & Root, so this should come as no surprise. The government gladly agreed, and Edgar set about to come up with a suitable design.

Edgar Miller (second from right) sits with friends, including John Holabird (second from left). Photo by Oscar and Associates.

We also know that Edgar loved to use animals as objects of his art, as they were a reflection of nature and he believed they brought us back in touch with our humanity. Even more so, since the sculpture garden was intended to be used by the housing project’s neighborhood children, it made even more sense to use animals as a way to engage the young minds. It took a while for Edgar, busily preoccupied with his other projects (notably the Normandy House restaurant design, and other small projects), and in the midst of housing moves himself, to come up with sketches and plans so that the government officials could approve them all. Daniel Ronan, Director of Public Engagement at the NPHM, provided us with extensive research he did into the back and forth exchanges between many key government officials, the architecture firm, the stone supplier, the sculpting firm, and Edgar. It is quite fascinating how cordial everyone was back then, often beginning letters with “My Dear So-and-So” and getting into robust discussions about the nature of the project and theories about art. We wonder if this would be possible in today’s climate of anti-intellectualism in Washington.

Original sketch of the Animal Court by Edgar Miller (courtesy Daniel Ronan, National Public Housing Museum)

One of the major points of contention was whether to use union labor in the execution of the sculptures. Naturally, Edgar would have wanted to do them himself, but since the WPA insisted the entire site be 100% union workers and all construction be on site, a workaround had to be found, since even the architects and government officials knew that the sculpting would need to be done by a skilled non-union artisan. Eventually they settled on a company run by a man named Charles Buhl, and the union agreed to let the work be done by these artisans as long as it was off-site, in a warehouse across town. Of course, this added some considerable moving expenses, but it also staved off any labor unrest on the project site.

The large bull sculpture, by Emmanuel Viviano, in the studio (courtesy Chicago Hisotrical Society)

Fast forward to the summer of 1937, and the animal sculptures were completed. It took three months to sculpt the six smaller, boulder-like sculptures, and the one large monumental sculpture of a cow and several cats. It has also been discovered, according to public housing researcher Elizabeth Milnarek, that the large sculpture was designed by an apprentice of Miller’s named Emmanuel Viviano. It is very hard to tell apart their styles, and clear that Edgar’s influence was profound. It’s also reasonable to assume that Miller had some critical influence on the design since it was his commission, so it was his reputation on the line.

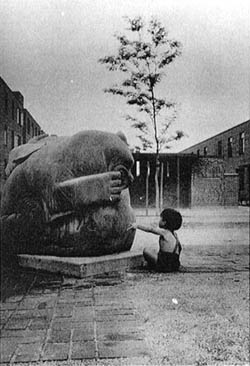

In any case, once the sculptures were unveiled and the Jane Addams Homes opened, the Animal Court was a smashing success. Not only were the sculptures fun for children to climb on top of and make believe with, but there was also an innovative reflecting pool and sprinkler system that ran through the center of the sculpture garden, providing much-needed relief in the summer months to hot children and their undoubtedly exasperated parents.

Chicago Historical Society

Over time, the sculptures began to decay, but the residents of the apartments always took care of them, providing new paint jobs from time to time to protect them from the elements. Still, after nearly seventy years of exposure to Chicago’s harsh winters and rambunctious children, by the early 2000s they were in a state of serious neglect. Meanwhile, the Chicago Housing Authority was on a mission to wipe clear as many of these old projects as they could as they had become outdated, run down, and seen as politically unacceptable in a new social climate hostile to large-scale affordable housing. The NPHM secured the rights to use the one remaining building of the thirty-two original apartment complexes, and to remove the sculptures from the site in the hope that they could be restored and preserved.

Modern day deterioration before the housing complex was demolished and the sculptures removed from the site

That project is still underway, and it is our sincere hope that eventually the sculptures will be restored to their former glory and the National Public Housing Museum gets to tell its part of history. According to Mr. Ronan, "The Animal Court sculptures at the former Jane Addams Homes are a touchpoint not only to the Taylor Street and Little Italy neighbors, but also advocates of art everywhere. Neighbors, Chicagoans, and Americans understand the importance of art in enriching and bringing together our communities and bringing together the stories we share." To learn more, and if you are interested in supporting, please visit www.nphm.org.