An Enchanting Visit to Oakridge Abbey

Hillside, Illinois

Recently we had the opportunity to visit the Oakridge Abbey in Hillside, Illinois, just outside of Chicago. Back in the late 1920s, Edgar Miller was hired to create a large assortment of stained glass windows for the monumental crypt, which was then touted as one of the most elegant and beautifully designed mausoleums in the area. In fact, it was and remains quite a magnificent structure.

The person responsible for its construction was Anders E. Anderson. Already a real estate developer, he decided to go into the cemetery business, and believed that a mausoleum would prove to be a lucrative venture while providing a serene resting place for people’s loved ones. He became president of the Oak Ridge Cemetery and then, in 1917— the year Edgar arrived in Chicago— proceeded to take out a loan for the mausoleum project from Chicago Title and Trust for $300,000, no small sum in those days (or today, for that matter).

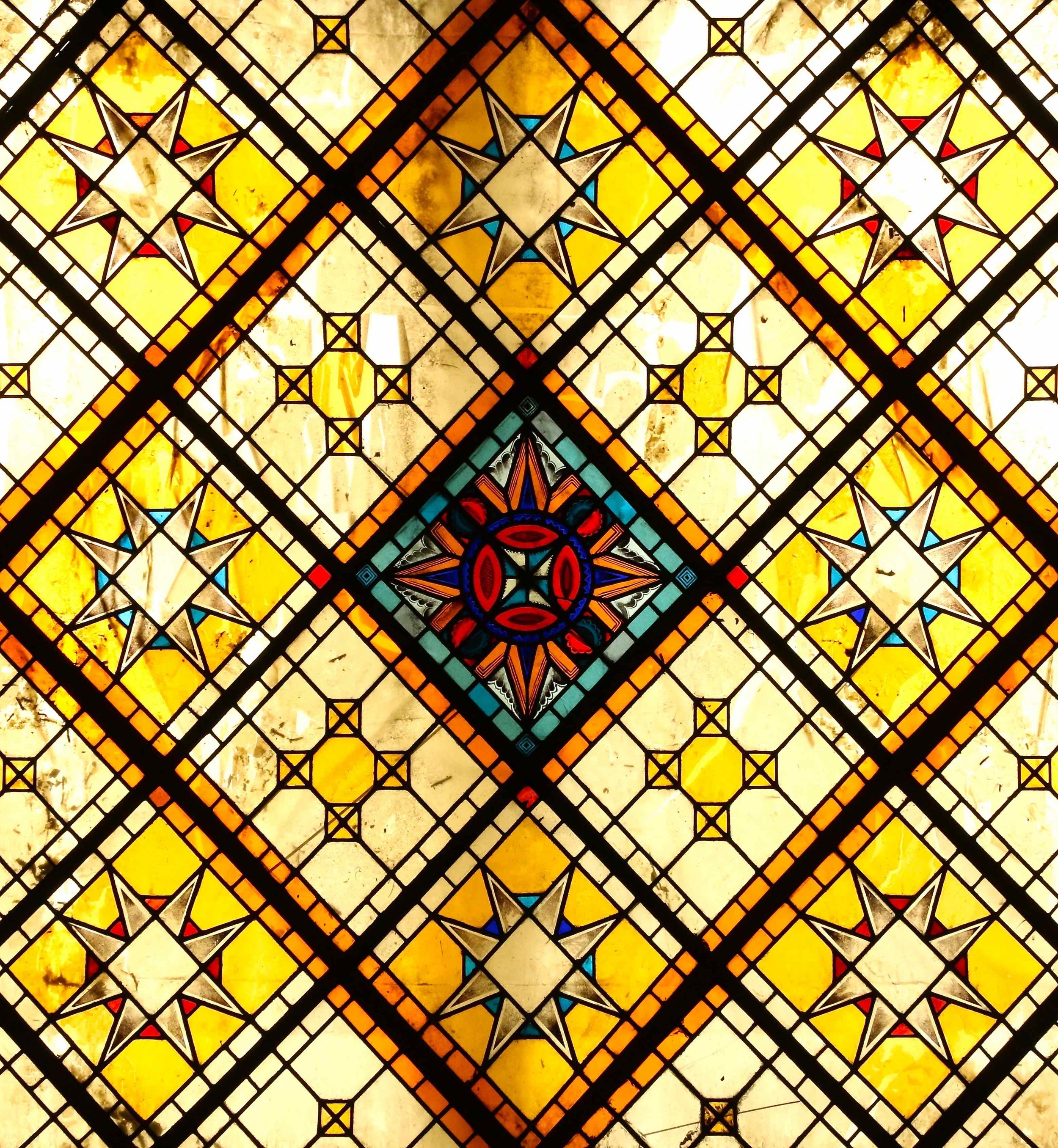

Detail view of the ceiling of the chapel

Wanting to do a project on a grand scale, Anderson even traveled to Europe in 1924 during the construction of the mausoleum to find artistic and architectural inspiration. Completed in 1928, it is not entirely clear when Miller was brought onto the project, but most likely his work there began in the mid-to-late 1920s and continued past the opening date of the building. Many of the windows appear to be commissioned by individual families, not just the cemetery itself. You can learn more about the history of the mausoleum and Anderson here, thanks to the research of Jim Craig.

Stained glass in the Anderson family crypt

Walking through the building is quite an experience in and of itself. It is two levels, with many hallways going off in different directions, and various nooks and stalls, some covered by curtains, which we had to peek through to see if there were any more hidden stained glass works.

Doors covered in stained glass

All in all, the abundance of Miller’s stained glass at Oakridge Abbey is far and away beyond anything else he worked on. While there are many great examples of Edgar’s stained glass work in other churches, public spaces, and homes, in no other place is there such an assortment of what has to be considered his finest work. Each window has its own sense of style and character, and within each set are so many rich details, down to hidden figures in corners of the glass, and various symbols and icons painted and etched in minute detail.

A religious scene depicted at the end of a grand hallway

Records of Miller’s receipts and pay stubs are non-existent, and it remains unclear who even hired him, though one might assume it was Anderson himself. It is worth remembering that at this very same time, Miller was concurrently working on the two projects in Old Town, the Carl Street Studios and the Kogen-Miller Studios. On top of all his other small projects and commissions, it is truly unbelievable that he was able to produce so much work in such a short amount of time.

A figure, with a noticeable "K" upon his lapel, is hidden at the bottom corner of a large stained glass window. Any symbolism experts know what this signifies?

That said, we know that his sister, Hester Miller, helped with these windows, most likely in painting the glass so that the work of individually hand-painting each pane would not fall entirely on Edgar's shoulders. That said, she insisted that Edgar be the only signer of the work, as she felt her contribution was merely as an assistant.

Detail of a dove

While the cemetery isn’t technically open to the general public, the staff in the office were delighted by our interest in the stained glass windows, and allowed us to wander around and explore the mausoleum.

Another private family window. Note the incredible detail in each piece of glass.

Unfortunately, many of the windows seem to be in a state of some disrepair. We realize fixing stained glass windows can be expensive, so it’s probably unlikely they will be restored any time in the near future. In the meantime, it’s probably just best to keep our collective fingers crossed that perhaps an emergent interest in Miller’s work will maybe one day encourage a preservation effort.

Another closer detail of a much larger window. Note the lion figure on the bottom right. Edgar Miller was always playful, even when faced with a project of such immense gravitas!